It is almost our favorite time of year here at the Fair Housing Project of CVOEO- Fair Housing Month!

Each April at CVOEO’s Fair Housing Project, we celebrate the 1968 passage of the Fair Housing Act with a series of public education and art events to raise awareness about housing discrimination in Vermont and the positive role that inclusive, affordable housing plays in thriving communities. To promote Fair Housing education and awareness, the Fair Housing Project facilitates a series of zoom webinars, Fair Housing workshops, and art activities, prompting participants to reflect on what Fair Housing means in their community.

Join us!

There are a variety of ways you, your community, or your organization can participate in the celebration this year, despite us being unable to meet in person. Our Fair Housing Month calendar is filling with events hosted by us and organizations across the state, including Fair Housing Friday zoom webinars, the Old North End Art Center’s art camps, and HeART & Home community art project, library book and film discussions, and Fair Housing workshops.

Let us know how you, your community, or your organization would like to participate by filling out this brief form.

(Of course, we anticipate these activities will be held remotely, and when possible, outdoors with physical distancing.)

Here are some examples of the variety of ways you can join us in celebrating Fair Housing Month:

- Host an event in your community focusing on the history and impact of the Fair Housing Act, local housing needs, or the value of diversity and inclusion in housing (which we will add to our Fair Housing Month event calendar)

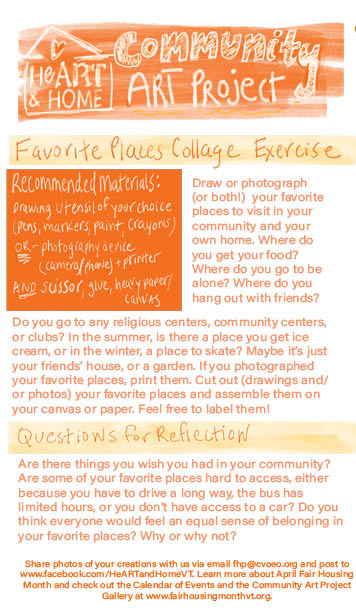

- Participate in the HeART & Home Community Art Project, or lead a HeART & Home Community Art activity in your community/classroom/organization

- Participate as a panelist in one of our three Fair Housing Fridays

- Invite us to do a Fair Housing workshop with your community/organization

- Start a discussion group in your organization or community (see list of books and films at https://libraries.vermont.gov/fairhousing2021)

This year we have a new partnership with the Vermont Department of Libraries and Vermont Library Association for new activities, like book discussion groups, story walks, and more at sites all over the state. Click here to learn more!

Are you curious about our HeART & Home Community Art Project? Check out a couple of the prompts we are sharing with our project participants.

For examples of past activities and to see this year’s full calendar of events (which will be posted later this month), visit www.FairHousingMonthVT.org.

If you are interested in participating in any capacity in our Fair Housing Month Celebration, please fill out this brief form.

Fair Housing Month activities in Vermont are coordinated by the Fair Housing Project of CVOEO, in collaboration with Vermont Department of Libraries, Vermont Library Association, ONE Arts Center, Vermont Legal Aid, Vermont Human Rights Commission, VT Department of Housing and Community Development, and other partners. This program is supported by a Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Fair Housing Initiatives Program grant and supported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, a federal agency, through the Library Service and Technology Act as administered by the Vermont Department of Libraries.

Fair Housing is the right to equal opportunity in housing choice and the right to rent, buy, finance, and live in a home free from discrimination or harassment. The federal Fair Housing Act prohibits discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, color, religion, national origin, sex, and as amended, disability and family status. This also covers harassment, including sexual harassment.

Vermont has additional protections based on age, marital status, sexual orientation, gender identity, receipt of public assistance, being a victim of domestic violence, sexual assault, or stalking, and denial of development permitting based on the income of prospective residents.

To learn more about your Fair Housing rights and responsibilities, visit www.cvoeo.org/fhp and see www.fairhousingmonthvt.org for April fair Housing Month details. Contact us at fhp@cvoeo.org.