It’s not every day that we can praise the New York Times editorial board for following in Thriving Communities’ wake. Saturday’s editorial, which borrows its headline, “The Architecture of Segregation,” from a study we posted about last month. The editorial, while noting this two summer’s “positive” developments – the Supreme Court’s disparate impact decision and HUD’s AFFH rule – rightly takes federal officials to task for failing, over many years, to enforce the Fair Housing Act. And the editorial invokes Walter Mondale’s comments at the HUD conference last week about how the act’s intent is “not fulfilled” by exclusionary land-use planning.

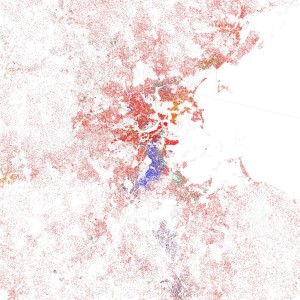

While government deserves a good share of the blame for the present state of residential racial segregation, there are those in the community of fair housing advocates who contend that the real estate industry has been at fault, too. How else to account for the fact that upper-middle-income black families don’t have comparable access to the neighborhoods where their upper-middle-income white family peers live.

Indeed, one factor that may have contributed to segregated patterns is the choice of many whites to opt out of integrated communities, as Stacy Seicshnaydre pointed out in a law journal article last year, “The Fair Housing Choice Myth.” And one way to address that, Seicshnaydre argued, is to defund exclusion — as application of the AFFH rule promises to do, at least in theory.

Meanwhile, HUD conferees were reminded last week, redlining is still with us, and new cases are in the pipeline.