- Portland, Ore., has come up with a new funding source for affordable housing: tourists!

The city council has voted to dedicate a share of the tax on Airbnb-type rentals to the city’s Housing Investment Fund — $1.2 million a year. That’s a drop in the bucket in a city where the affordable housing shortfall amounts to about 24,000 units, but it’s better than nothing.

The city council has voted to dedicate a share of the tax on Airbnb-type rentals to the city’s Housing Investment Fund — $1.2 million a year. That’s a drop in the bucket in a city where the affordable housing shortfall amounts to about 24,000 units, but it’s better than nothing. - Jackson Hole officialdom has agreed to consider a plan that would dial back commercial growth in favor of housing, with density bonuses offered for workforce housing. A citizen campaign bearing slogans like “Housing not hotels” apparently got a receptive hearing.

- The Republican leadership of Howell, N.J., is backing an affordable housing project despite, and in the face of, some unusually ugly civic opposition — in a state where support for affordable housing is typically associated with Democrats.

This profile of courage, in the Atlantic, includes a fine summary of the tortuous (and torturous) fate of affordable housing in New Jersey after the landmark Mount Laurel decisions. Another example of how good intentions and a supportive legal infrastructure are not enough.

This profile of courage, in the Atlantic, includes a fine summary of the tortuous (and torturous) fate of affordable housing in New Jersey after the landmark Mount Laurel decisions. Another example of how good intentions and a supportive legal infrastructure are not enough. - The “recapitalization” of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, as proposed by two economists, would direct a flood of new money to the states for affordable housing via the Housing Trust Fund and the Capital Magnet Fund.

Vermont would get $4.6 million a year for affordable housing for 20 years under this scheme. Sounds great, but whether this proposal has any legs is an open question. Some members of Congress would just as soon do away with Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae altogether.

Vermont would get $4.6 million a year for affordable housing for 20 years under this scheme. Sounds great, but whether this proposal has any legs is an open question. Some members of Congress would just as soon do away with Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae altogether. - A community of 15 tiny houses is scheduled to open later this month in Seattle to provide transitional quarters for homeless people. Granted, this isn’t exactly cheerful news, but at least it’s different.

Tag Archives: Portland

Unease Down East

Burlington and Portland, Maine, have a few things in common. They’re the biggest cities in their states, they both pride themselves in their trendy livability (as measured by magazine rankings, food-trucks per capita, those sorts of things), they both experienced negligible development of rental housing for many years, they both worry about gentrifying neighborhoods, and they both have a housing affordability problem.

Portland’s problem might seem a bit more acute, thanks in part to a six-part series in the Portland Press Herald that elaborates on what the mayor-elect calls a “housing crisis.”  The themes echo other crises around the country – soaring rents (up 40 percent over the last five years), stagnant or declining incomes, middle-income renters priced out and fleeing to the burbs.

The themes echo other crises around the country – soaring rents (up 40 percent over the last five years), stagnant or declining incomes, middle-income renters priced out and fleeing to the burbs.

The average two-bedroom apartment in Portland, according to the newspaper, is $1,560. That’s too bad, because an apartment like that is out of reach for anyone with a housing voucher. HUD puts the fair-market rent for a two-bedroom in Portland at $1,074 – which happens to be well below Burlington’s $1,309. What’s more, landlords in Portland can capitalize on the hot rental market by charging non-refundable application fees, which their counterparts in Vermont cannot.

How Portland is going to relieve its “crisis” is an open question. The mayor-elect has appointed a committee. The city is examining municipally owned land with an eye toward potential sites for affordable housing. New developments are supposed to make some units affordable for middle-income renters, but that inclusionary policy apparently doesn’t extend to the working poor. Here, as elsewhere, the remedies seem to pale before the problem.

Housing notes from all over

- Before you dismiss the idea that shipping containers can be used for housing, consider this student-housing complex in Amsterdam, as described by The Guardian. Can you imagine something like this on the northwest corner of Burlington’s Main Street/S. Winooski intersection, which has been suggested as a possible site for privately developed UVM student housing?

- The City Council in Portland, Ore., where a “housing emergency” has been declared and where rents have risen more than 20 percent over five years, boosted the city’s affordable housing fund by $64 million. The money comes from a property-tax set-aside, and the council is looking for more revenue sources.

And one of the councilors has lofted an idea that some other cities beset by under-used mega-athletic complexes might want to seize upon: sell the Portland Coliseum for to a developer who will put affordable housing in its place.

And one of the councilors has lofted an idea that some other cities beset by under-used mega-athletic complexes might want to seize upon: sell the Portland Coliseum for to a developer who will put affordable housing in its place.

- As we’ve noted before, the nationwide initiative to affirmatively further fair housing calls for affordable housing development (at least a good share of it) in low-poverty, “high-opportunity” areas. A country club would seem to fit that description, at least generically. So we were interested to learn that the Planning Board in Mahwah, N.J., recently approved the redevelopment of a country club there for affordable housing.

Before you get too excited, though, you should know about the downside: Much of the land is contaminated from years of pesticide spraying, and the cost of remediation (which includes removal of hundreds of trees) contributed to a reduction in development’s affordable capacity: down from 350 multi-family units to less than 100 single family homes.

- Uber will deliver $1 million to Oakland’s affordable housing fund for the privilege of turning a former Sears building into an office space.

The deal was prompted partly by fears that Uber’s corporate arrival, with an anticipated 3,000 employees, would lead to gentrification and even higher housing prices.

The deal was prompted partly by fears that Uber’s corporate arrival, with an anticipated 3,000 employees, would lead to gentrification and even higher housing prices.

- Attention, City Market, Hunger Mountain, et al: A food co-op in affordability-challenged Asheville, N.C., is contemplating adding affordable housing to its expansion plans, which also (and less intriguingly) include enlarging its existing store, parking lot and office space.

- Speaking of parking, the Berkeley City Council has voted to target underused parking-lot space for affordable housing development.

Council members were reminded at the meeting that the average cost of a 1 bed-room apartment is $1,400 a month, and that’s under rent control! The average cost of an apartment not under rent control? $3,256 a month.

Council members were reminded at the meeting that the average cost of a 1 bed-room apartment is $1,400 a month, and that’s under rent control! The average cost of an apartment not under rent control? $3,256 a month.

Stuck in the middle

Middle-class financial struggles have occupied the public discourse for some time, but wouldn’t you know, we’re starting to hear more about housing unaffordability as a stresser for this beleaguered population segment.

The annual “State of the Nation’s Housing” report from Harvard took note this summer:

While long a condition of low-income households, cost burdens are spreading rapidly among moderate-income households. The cost-burdened share of renters with incomes in the $30,000–45,000 range rose 7 percentage points between 2003 and 2013, to 45 percent. The increase for renters earning $45,000–75,000 was almost as large at 6 percentage points, affecting one in five of these households. On average, in the ten highest-cost metros—including Boston, Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco—three-quarters of renters earning $30,000–45,000 and just under half of those earning $45,000–75,000 had disproportionately high housing costs.”

Granted, much of the news about middle-class housing unaffordability is coming out of the big cities – places where “middle income” is construed to reach far above Vermont standards. For example, Cambridge, Mass., is taking steps to reserve a share of “affordable” housing in a new Kendall Square building for families with incomes in the low six figures! San Francisco is also considering measures that would expand affordable housing eligibility and help out renters in the $100,000 to $140,000 bracket. And Portland, Ore., where the “housing emergency” is apparently wide-ranging, is looking at a form of inclusionary zoning that make apartments available to people making 100 120 percent of the median income (Up to $96,875 for a family of four).

Perhaps it’s a testament to the severity of the housing crisis around the country, and/or to the fragility of the middle-income stratum, that the terms “middle class” and “subsidy” are suddenly being spoken in the same breath.

Here’s the thing: To qualify for most subsidized housing, applicants can’t earn more than 80 percent of the local median income. Where does that leave people who draw an average salary, or perhaps a little more? Perhaps in a place where they can’t readily afford housing but can’t get any help, either. How many such people there are in Vermont is unclear; plenty, no doubt.

(Note: Middle-income earners are not beneficiaries of Burlington’s inclusionary zoning ordinance, which aims to provide affordable rentals for people earning up to 65 percent of the median; and for sale, up to 75 percent.)

For an illustrative display of how housing costs compare to standard incomes, the National Housing Conference’s interactive “Paycheck to Paycheck” shows bar graphs for each of the nation’s metro areas – and just one in Vermont, Burlington/South Burlington. One graph compares salaries to the pay needed to afford a median-priced home; another does the same thing for 1- and 2-BR apartments at HUD’s “fair market rent.”

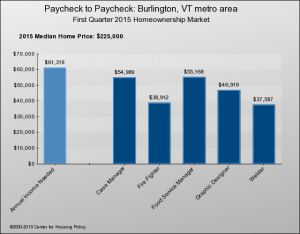

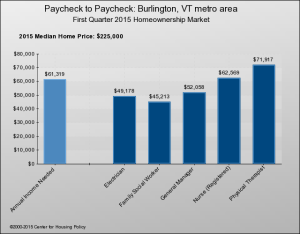

Below are the charts for 10 occupations that might be considered to be middle class. As you can see, eight of the 10 would be hard pressed to afford purchase of an average home in Burlington:

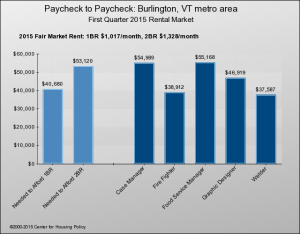

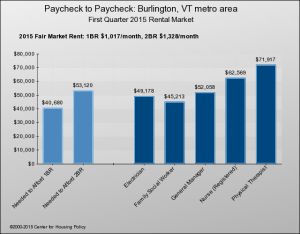

They do a little better in the rental market, but still, six of 10 can’t comfortably afford a two-bedroom apartment in Burlington:

An affordable-housing outlier

A common refrain in the national “conversation” about the affordable housing crisis, or shortage, is that development of new multi-family rentals is, well, costly … even unaffordable, in some cases.

One standard cost we’ve seen bandied about is $200,000 per unit. That’s the figure set out in the Windham & Windsor Housing Trust’s treatise on this topic, “Why does it cost so much to construct affordable housing?”

The other day we stumbled across an article about a developer in Portland, Ore., who operates on a different model — tight scheduling, efficiency, no frills, and remarkably, all-private financing — without public subsidies. The result: a unit cost of around $70,000. Here’s a glimpse:

We can’t vouch for the economics of this, but the website of the developer — Home First Development — links to an article, “Building affordable units for less,” that offers a thumbnail accounting of the approach taken with a 27-unit apartment complex built for $1.89 million. This development is in east Portland, a few miles from downtown, so we presume the land was less costly than for a comparable site close in.

Another, more recent development, also in east Portland, comprises 78 one- and two-bedroom units that rent for $395 to $775 a month, according to the news story that sparked our interest. The cost of building that project? $5 million.

In each case, the developer began by estimating how much low-income tenants (e.g., $24,000 a year) could afford to pay for housing, then worked through the financing with that constraint.

Might such a model be replicable? You be the judge.