As someone who has attended many housing conversations over the past decade, there are many housing-takes I am well acquainted with. If you’re a housing advocate, this is probably true for you, too.

We are all familiar with the proverbial “three legged stool” of affordable housing (capital investments, financial assistance, and supportive services), the plight of housing being siloed from other social service sectors, Vermont’s aging demographics, and smart-growth practices. If one were to create a housing bingo card, terms like “Frannie Mae and Freddie Mac,” “multi-family housing,” and “Act 250″ would surely make it into squares. Combined with our notorious habit of referring to the numerous housing nonprofits, agencies, and other entities by their acronyms, the world of housing has developed its own language. If you are anyone outside of our insular bubble, however, all this terminology likely requires some translation.

Last year, we shared this post “Housing Committees & Citizen Housing Advocacy. Our intent for the guide was to encourage participation in local housing committees by everyday people who can speak to the individual, specific needs of the community members most impacted by our housing shortage. But if we don’t make the “language” of housing more accessible, can we rely on community-driven change by our housing committees and review boards?

Opportunities for community engagement in the policies we implement as towns, cities, and states are in place with the belief that they create avenues for community members to ensure their needs and shared spaces are not steamrolled by national, government policies.

We know that all cities and towns don’t have the same needs, and a single overseeing organization could not possibly know what those needs are. We also know the history of our federal and state governments creating intentionally discriminatory policies with the intent of disinvesting from Black and Brown communities, and segregating their members from white communities. This is to say that existing regulations, like the National Environmental Protection Act, are intended to further our democracy through community participation.

What ends up happening however, as this NYTimes podcast points out, is that the marginalized communities intended to benefit from these policies are not the ones actually using them. It is the people with the privilege of access to these avenues who are most readily able to voice their concerns — people who have the time to do the research and commit to the meetings, the backgrounds to understand the language, access to the meetings space through transportation or technology, familiarity with governance protocols, and the personal interest to “protect” their stakes in their neighborhood.

In recent years, housing advocates have recognized this pattern. Already, there are creative solutions emerging across Vermont to bring the housing conversation to the people passionate about housing justice, but lacking avenues to make an impact.

Housing for All Summit

The Fair Housing Project joined Vital Communities and Keys to the Valley for the recent Homes for All Summit, a conversation on how to meet the housing needs of the Upper Valley Region of Vermont.

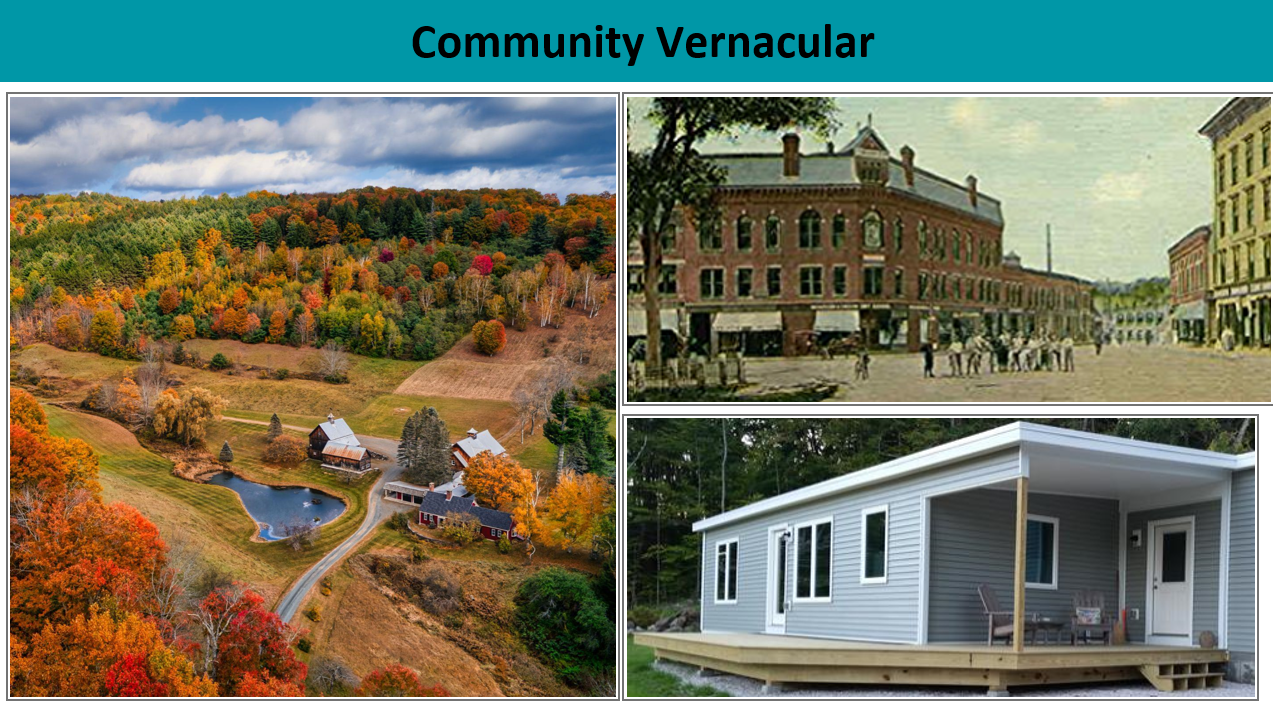

Together, we discussed housing solutions, projects, and challenges Upper Valley communities are facing. John Haffner, manager of Vital Communities Housing and Transportation program, emphasized the need to change our vernacular when we talk about housing and communities in Vermont’s more rural spaces.

Two photos from the Upper Valley region appeared on Haffner’s screen. To the left, an idyllic single-family house with a red barn, surrounded by rolling pastures and foliage-adorned hills. To the right positioned a black and white photo of a bustling city center, complete with front-facing businesses, topped by apartment rentals and connected by walkable roads.

Haffner argued that not everyone can live in the single family home, abutted by the red barn and rolling pastures that comes up when you google “Vermont Upper Valley,” as he revealed was the case with the Norwich-based photo on the left. However, dense, walkable town-centers are just as much a part of Vermont’s historical “character.” The right-hand photograph Haffner reveals as Lebanon town from the early 1900’s, ironically encompassing our new urban ideals over a hundred years past. The strongest resistance to building the housing we need is often in the name of preserving the character of our communities. But character becomes distilled into a series of images that may not actually represent the true diversity of our Vermont neighborhoods. Housing advocates are charged with shifting our shared perception of what it looks like to live in the Upper Valley region of Vermont.

In Burlington, the Department of City Planning Brings the Housing Conversation to the Community

Up in the Chittenden County region of our state, housing advocates deal with distinctly different housing needs, but are facing a similar problem: community resistance to building in their neighborhoods. Can you shift the way a community thinks about their current housing landscape, its history, and its future over a series of public forums?

Burlington’s Department of City Planning is responding to Vermont’s most acute housing shortage, where recent vacancy rates have dropped to 0.4% for rental housing overall, and as little as 0% for three bedroom apartments. One of the zoning blocks they are charged with reviewing is the South End, the Pine Street corridor which includes Burlington’s Arts District.

City Planning staff members Meagan Tuttle and Charles Dillard are tiptoeing in delicate territory, however. With the area only recently formally recognized by the city in 2010 as the Arts District, artists have been organizing in the remains of Burlington’s manufacturing companies for over 30 years. Artists are credited with revitalizing a part of town zoned only for manufacturing, and bringing some of the “funky personality” that we associate with Burlington today. But in 2015 when Burlington proposed housing in that area, the businesses and artists organized against it with some success. Today, under the guidance of Tuttle and Dillard, the rezoning proposal looks a little different. They have identified what is termed the “Innovation District,” a small parcel of land near the Arts District that would benefit the community with more housing.

The Planning Department of Burlington was cautious and strategic in how they engaged the community around this potential change to regional zoning. A series of interactive Q&A’s allowed residents to ask questions about the proposed change, and to voice their needs for the community, including an interactive map which people could add notes to. The team was a frequent visitor at the Farmers Market, a well-attended community event that takes place in the Arts District.

Is it possible to talk about zoning, but make it fun?

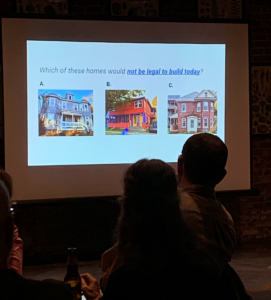

At the start of last month, the Burlington Department of Planning hosted a trivia night at Burlington Beer company. The audience was an even split of housing advocates, curious for “fun” ways to consider housing policies, and patrons, entertained by the prospect of trivia while enjoying a drink. Surely, there has never been a moment in Vermont’s history where the conversation of zoning was accompanied by so much laughter. Hosts asked questions like, “how many units are in each building?” showing an array of “charming” homes that had been subdivided into multi-family housing. Between questions that invited audiences to reflect on the history of Burlington’s housing policies, moderators encouraged the audience to reflect on how different neighborhoods in Burlington were more or less inclusive. “As we play this game, think about how Vermont has both one of the oldest housing stocks in the country, and continues to be one of the whitest states in the country.”

Noteworthy in the outreach methods of Burlington’s Office of City Planning is their visual iconography. If one is asked to draw a picture representing “home” (as we often prompt Fair Housing Month participants to do at CVOEO’s Fair Housing Project), most of the time, it is depicted as the iconic square topped by a triangle. This is true even if the artist themselves does not live in a place represented as such, with the exception being when participants are invited to consider home from a deeper, more personal lens, as with this Bent Northrop Fair Housing Month submission. Burlington’s City Planners know that the iconic “single-family” two bedroom house is not what most Burlington community members live in, and so they hired local artist Jodi Whalen to depict the specific, unique architecture of buildings in Burlington. Whalen’s drawings include some of the quirky apartments featured in the trivia slides- which appear as a single home, but pack extra apartments in the back – as well as the newer, high-density builds that are cropping up in the city today. We reached out to Whalen to hear more about the process of creating the illustrations.

I moved to Burlington from Pennsylvania in 1991, and have lived in the Old North End, Downtown, the New North End, and the South End. I love not just the unique architecture of the city, but also the way people make their houses their homes. I love to ride my bike around town to catch glimpses of porch gardens, little free libraries, sunflowers in green belts, and other touches that bring these old homes new life. In my illustrations, I like to add whimsical colors and patterns to add even more of the fun Burlington spirit to the homes.

-Jodi Whalen, on her illustrations for the City of Burlington Department of Planning

This is just a taste of some of the creative approaches to shift our housing “vernacular” as towns, cities, and a state. Tune into our Vermont Housing Conference post for highlights on other creative takes to inviting more community members into the housing conversation!